“Science and art ask the same questions.” — Lawrence Krauss, theoretical physicist and cosmologist.

Leonardo da Vinci was an artistic as well as a scientific genius of the Renaissance period when the study of art and science was not perceived as separate fields. The world also has seen great achievers in the field of science such as Albert Einstein and Richard Fenyman who were scientists as well as artists at the same time. A scientist being a serious artist is a rare phenomenon today. The number of scientists using arts to assist in their research or science communication is still a minority.

While there are a handful of scientists in the field of Ecology like Nalini Nadkarni, the well known canopy biologist who reaches out to the non scientific audience through art to create awareness on Forest Canopies, Mike Shananan is a rare class of ecologist who harbours a seamless amalgamation of science and the arts. His passion and creativity have led him to research on rainforests, to inking of figs, and to set it down in words for people in his blog and books. His inquiries into ecology, conservation, science communication and visual art continue to build a lucid knowledge base for ecologists, teachers, artists and society.

Artecology is pleased to be collaborating with him for the movement based exploration on, ‘How to be a fig?’. We share some of our conversations here.

AI: You are a well-known ecologist and an author, what drives you towards Nature?

Mike: I like its movement, its energy and its unpredictability. You never know what you’ll find beyond the next tree. Being in nature is enlivening and grounding.

AI: Any memorable experiences from your childhood you would like to associate with your love for nature? Were those experiences instrumental for you to become a rainforest ecologist?

Mike: My affinity for forests must be due in part to me playing among trees in woods as a child. My Dad’s love of nature rubbed off on me too. We watched a lot of David Attenborough’s documentaries together. They helped instil in me a desire to travel to distant places. I liked biology at school and went on to study it at university, but it was not until I first walked in a tropical forest — in Sri Lanka — that I realised where I wanted to spend my time as an ecologist. I was awestruck.

AI: Your research on figs and the animals that eat figs is a landmark one. How did you get interested in figs?

Mike: It was a lucky break. For my master’s degree project in 1997 I was meant to go to Indonesia to study the wild bird trade but the project fell through. My supervisor was a fig biologist and he asked some colleagues whether they could host me for my project. Rhett Harrison replied and I went to his field site in Malaysian Borneo, in a national park that is home to about 80 fig species. I started studying them and the birds and mammals eating their figs. The fig trees, especially the strangler figs, were feeding a huge proportion of the national park’s wildlife and so were sustaining the seed dispersers of many other plant species.

AI: Your unique book on the story of figs is a classic in itself. What made you write it? How has the response been so far for the book? Has your book influenced conservation of fig trees?

Mike: I couldn’t NOT write it. The more I learned about fig trees, their extraordinary biology and their disproportionate impact on ecology and human culture, the more I wanted to share my sense of wonder.My book has led to some new connections with researchers who are using these trees to address deforestation, conserve wildlife, limit climate change and improve people’s lives. It’s too early to say what its impacts are, but I am happy with the feedback I have had from readers who say they have enjoyed it.

AI: Would you like to share with us your growth as a writer?

Mike: I feel like I’m still just at the start of that growth. I’ve always liked writing and I have worked as a journalist and in research communication, but it is only recently that I’ve really started to understand the craft. I’ve written a non-fiction book with narrative form but my goal is to write fiction.

AI: You have dabbled in art too. What made you foray into that field? Do you have any formal training?

AI: You have dabbled in art too. What made you foray into that field? Do you have any formal training?

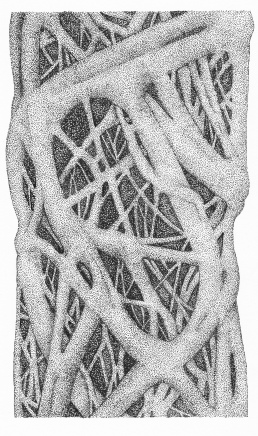

Mike: From a very young age, I’ve always liked drawing. I’ve had no training and it has always been for my own entertainment than anything else.There’s so much freedom in a blank page and a sharp pencil.

AI: Do you follow any particular style to create illustrations? Any particular medium you prefer?

Mike: I usually use 0.1 and 0.3 millimetre black pens and a lot of dots. I am going to start painting this year. It is time for some colour.

AI: What do you think about art for conservation?

Mike: Like all art, some of it is good and some of it is bad, by which I mean some of it evokes an emotional response that is positive and some of it fails to make a mark or even has a negative overall impact on those who view it. Often it is a fine balance. I liked Ralph Steadman’s new paintings of endangered animals in the book Critical Critters. His ink and paint spatters communicate the violence that threatens to overwhelm them.

AI: When you started on art and illustrations for conservation was it a love for artistic expression, or was it more of a visual tool to create awareness and change?

Mike: I have mostly done illustrations to accompany educational material, and more recently for books, but the impetus has always been drawing for the pleasure of it.

AI: Would you please share your views on how your artistic expressions and your deep interest in conservation have emerged?

Mike: I’m interested in conservation, but far from certain what I think about it. I am still looking for answers to my questions about nature and our place in it.

AI: Do you think art and science complement or do the two areas compete against each other?

AI: Do you think art and science complement or do the two areas compete against each other?

Mike: Art and science are both forms of magic born of human ingenuity. They are siblings. There is much science in art and science would not be what it is without an abundance of creativity. They can be complementary forces, as when scientists and artists meet and collaborate to communicate. There’s no good reason to force them into opposition.

AI: There seems to be a wide communication gap between scientists and general public. What do you think is the reason for this? Do you have any thoughts as to how this awning gap can be bridged across?

Mike: Science is for everyone, but I think people are often led to believe that science is only for a minority and is too complex for everyone to understand. Scientists get criticised for how they communicate but we can’t expect them all to excel at it. That’s why intermediaries are so important – teachers, journalists, artists and others.

AI: Are there any particular stories/anecdotes/ philosophy/ advice that you would like to share with us?

Mike: Ecology teaches us that everything is connected, and that the relationships among things matter as much as, if not more than, the things themselves.

AI: Your thoughts on your collaboration with Artecology on the ‘How to be a fig? – movement performance project?

Mike: It is a huge honour to have inspired such a creative idea. I’ve seen some photos of some of the work in progress and I can’t wait to see how the performance turns out. The figs are such amazing lifeforms, in terms of their biology, their appearance and their importance to ecology and to diverse cultures. I think it is great that Artecology in collaboration with Veena Basavarajaiah will be using moving human bodies to portray the fig trees and some of their story, and especially great that this will be for an audience of scientists. And I love that the title of the piece “How to be a fig” is the same as that of a classic research paper published in 1979 by tropical ecological Daniel Janzen.

Mike’s book was published in 2016 as “Gods, Wasps, and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees” in North America, and as “Ladders To Heaven: How fig trees shaped our history, fed our imaginations and can enrich our future“ in Europe.

Reblogged this on Green Seeds and commented:

I met Mike Shanahan in my nascent years of the journey through the maze the end-of-year global climate change negotiations can be. In true Shanahan style, he served as a guide to me and many other journalists, ensuring we were able to make sense of it all, and in the interest of our diverse publics. Today, we are regarded as pros and that is thanks to him and the great team of Climate Change Media Partners, as they were known. Mike continues to inspire, this time, where art meets science. Cheers, Mike. Figs rock! I see that.

LikeLike